We often hear that New Zealand has an abundance of renewable energy. If you live in Taranaki like me, phrases like ‘Saudi Arabia of wind’ and ‘Power to X’ might ring a bell?

Yet power cuts and rising fuel prices continue to cause havoc. The Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment’s Briefing to the new Energy Minister warns, “We face growing energy security and reliability challenges”. MBIE expects even lifting the 2018 ban on petroleum exploration outside of the onshore Taranaki region would not restore investor interest. The government is working on measures to overcome investment barriers, especially in gas exploration and supply as it becomes “increasingly uneconomic”, or dare I say, “less profitable”.

What? The government wants to make fossil fuel investment more profitable and keep the gas burning, in a climate emergency? What about the billions of dollars lost in homes, businesses and infrastructure destroyed by mega storms, and the immeasurable costs on affected communities? For people living in Taranaki ‘Gasland’, it means even more seismic blasting with explosives, more drilling, fracking, flaring, deep well injection and dumping of wastes, threatening their lives and wellbeing.

A decade ago, there were heated debates over the practice of ‘landfarming’ where drilling wastes are spread on Taranaki farms for supposed natural remediation. In 2015, Fonterra refused to take milk from new ‘landfarms’. That did not stop the controversial practice, despite impacts on water quality, soil health and New Zealand’s reputation as a safe food producer. The ‘landfarms’ are now either full or nearly full. The Remediation NZ composting site in North Taranaki, with a stockpile of over 20,000 tonnes of petroleum and unauthorised wastes, has severely degraded the health and mauri of an ancestral awa of Ngāti Mutunga. It remains a sickening nightmare for neighbours, and a wicked problem for the regional council. What then?

Here the message is loud and clear, “Taranaki does not want to be a sacrificial zone anymore.”

One of those investor friendly measures MBIE has in mind is carbon capture, use, and storage (CCUS) to “allow for the development of reserves that would otherwise be uneconomic under the Emissions Trading Scheme due to a high concentration of CO2.”

CCUS is a distracting smoke screen, a band-aid over a gaping wound. When applied by the fossil fuel industry, it prolongs production and ignores the still rising emissions from its combustion. As the World Resources Institute put it, “Lowering emissions associated with production does not reduce the emissions from these fuels when they’re ultimately combusted… the use of CCUS should not be seen as a license to perpetuate the use of fossil fuels- particularly in the power sector where many other options are commercially available today.” Science advisers to the EU cautioned that neither the technology nor the governance and regulatory system is ready, and the reliance on CCUS is dangerous. Globally most CCUS projects in the past three decades have failed, squandering precious time and resources including public funding.

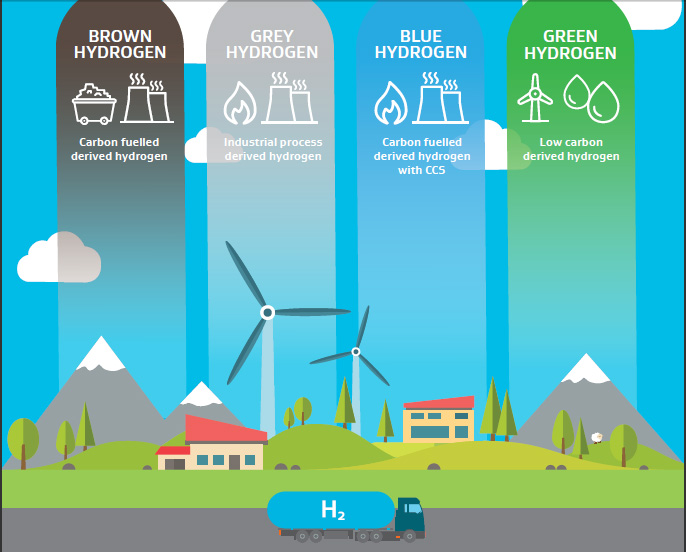

Worryingly, MBIE’s briefing supports the “development of hydrogen technology to produce hydrogen from natural gas without co-production of CO2.” This would likely involve CCUS, rendering the hydrogen ‘blue’. It would also prolong, even exacerbate, fossil gas reliance, along with harm to the local environment and people of Taranaki.

‘Green hydrogen’ got only one mention in the 45-page briefing. Perhaps MBIE took note of Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Simon Upton who warned that the focus on a green hydrogen economy could make achieving NZ’s climate commitments more difficult? Or the prohibitive costs associated with it have become obvious?

The government is, however, keen on “progressing an offshore wind regime at pace”. This is despite the uncertainties around potential renewable energy generation onshore, future electricity demand, and whether new energy-intensive industries and/or a renewable energy export market are pursued. Moreover, the Department of Conservation, in the 2023 Ara Ake Offshore Renewable Energy Forum, raised numerous concerns about large scale offshore wind energy development. These include inadequate baseline data for impact assessment, existing pressures on NZ’s unique biodiversity and the environment’s capacity to absorb additional impacts.

Still, at pace it is! The new government is now pushing full steam ahead for a ‘one-stop-shop fast-track consenting regime’ through a Bill to be introduced in Parliament by March 8 (or as early as the 5th). The intent is to “supercharge NZ’s infrastructure and economic potential… lift productivity, and grow our economy”. In a letter to stakeholders, RMA Reform Minister Chris Bishop wrote, “There will be a process for the responsible minister to refer projects for acceptance into the fast-track process, and the bill will also contain a list of projects that will be first to have their approvals granted.” The stand-alone Bill would thus have far-reaching ramifications beyond the remit of the Resource Management Act and Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf Act, at the expense of the environment, Māori rights and democracy. Long-term Taranaki locals see it as ‘Think Big’ all over again, and lament over yet more collateral damage to come.

Will fast-tracking large scale energy proposals, renewable or otherwise, ensure energy security for families and communities? My view, having researched the subject in Taranaki for over a decade, is no, unless priorities are reset to ensure energy equity, accessibility and resilience for people and communities, rather than to satisfy energy-intensive industries, export and economic growth.

In between the many redacted ‘free and frank opinions’ and ‘confidential advice to Government’, one line in the briefing strikes a chord, “The nature and scale of the challenges mean that the market may not solve them all alone.” Indeed, the challenges we face, the looming polycrisis of climate, ecological and social collapse, are immense. We live on a finite planet and with universal biophysical limits. The sooner we accept this and downsize our energy and material demand, the better.

By Catherine Cheung, Researcher, Climate Justice Taranaki, 1 March 2024