Published in the Taranaki Daily News, 1 November 2024

Catherine Cheung is an ecologist and researcher for Climate Justice Taranaki

OPINION: Catherine Groenestein’s reporting (Taranaki Daily News, 26/10/24) on a recent paper in the Journal of the Royal Society of NZ (Hale et al. 2024) is timely.

The paper lays out some of the risks from offshore wind energy development on our globally significant seabird and marine mammal fauna, and the potentially wide-ranging effects on food webs and fisheries. It highlights the deficits of baseline data and the need to incorporate Māori perspectives and adhere to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Beyond the scope of that paper are implications from the onslaught of energy-intensive mining, mostly overseas, to extract and construct components of wind turbines and other so-called “green” renewables.

The International Energy Agency (IEA, 2022) warns that the shift to a “clean” energy system will drive “a rapid rise in demand for critical minerals – in most cases well above anything seen previously – poses huge questions about the availability and reliability of supply”.

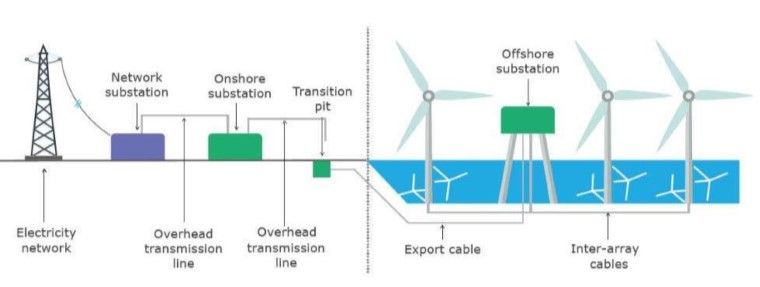

One key metal is copper. Offshore windfarms require up to 10 tonnes of copper per megawatt (MW) installed capacity, twice that of onshore installations (Bolson et al. 2022).

Taranaki Offshore Partnership’s proposed 1GW offshore windfarm (Stuff, 10/10/2024) could require 10,000 tonnes of copper.

The life-expectancy of a wind turbine is 25-30 years, after which we will face decommissioning and end-of-life waste management issues, and the costs and materials needed to replace it.

Globally, ore quality of several minerals is falling, e.g. copper ore grade in Chile has declined by 30% in the past 15 years (IEA, 2022).

Lower-grade ores require more energy, i.e. fossil fuels, to extract.

The IEA acknowledges that mineral mining comes with environmental and social challenges.

Ironically, mining assets are exposed to growing climate risks, e.g. copper and lithium mining is vulnerable to water stress exacerbated by climate change.

Governments the world over, including New Zealand, say that we must massively expand renewable energy supplies to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Some commentators say the sacrifice is worth it for the climate benefit. But can we thrive in a liveable climate without clean freshwater and healthy oceans?

This intricately connected biosphere that supports us and our non-human co-inhabitants is hanging in the balance.

We are trying to “solve” the climate crisis while ignoring all the other problems and constraints.

I’m not suggesting that the status quo of fossil fuel reliance is better than a shift to renewables.

I’m simply highlighting the reality that even “clean green” energy is not entirely clean or even renewable.

Given that we live on a finite planet with depleting natural resources and increasingly chaotic climate – how much more should we be extracting from it? What should a wise and responsible nation be doing instead? What would mokopuna-focused decisions look like?

In January 2023, the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment wrote to the then-Minister of Energy and Resources, urging that a whole-of-system energy strategy be formulated before the end of 2024.

The Commissioner emphasized that it would “require a comprehensive understanding of the environmental, economic and climate impacts that these various projects will have should they become part of the energy system”.

“Only then will we know whether the energy system that emerges will be low-carbon, secure and affordable (PCE, 2023).” So far this energy strategy has not materialised whilst numerous other policies and law changes have, many ‘under urgency’.

In August, the Office of the Minister for Energy acknowledged in a Cabinet paper that “the role of offshore wind in our future energy mix is unclear” (MBIE, August 2024). Yet it is progressing “at pace” an offshore renewable energy regulatory framework to “give developers greater certainty to invest” and is considering a developer-led approach.

Costs on ports and transmission upgrades are estimated at $320-$720 million and $120-$160m respectively (PWC, 2023).

Notably, there is already 4.275 GW of onshore wind projects in the pipeline (NZ Wind Energy Association website, accessed 28/10/2024).

In addition, the Draft Minerals Strategy aims to double NZ’s mineral export to $2 billion by 2035.

The infamous Fast-Track Approvals Bill overrides essential environmental protection and democratic processes, resurrecting zombie projects turned down by courts.

It now paves the way for Trans-Tasman Resources to mine our seabed near the underwater gardens off Pātea so beautifully illustrated by Karen Pratt of Project Reef (TDN, 28/10/2024).

Offshore wind companies are also eligible for Fast-Tracking once the offshore renewable energy regulatory framework is in place.

Companies have been quick to stake claim to the world-class wind resource in the South Taranaki Bight, also emphasizing the incompatibility with seabed mining (RNZ, 25 Oct 2024).

This reminds me of the African proverb: “When two elephants fight, it is the grass underneath that suffers.”

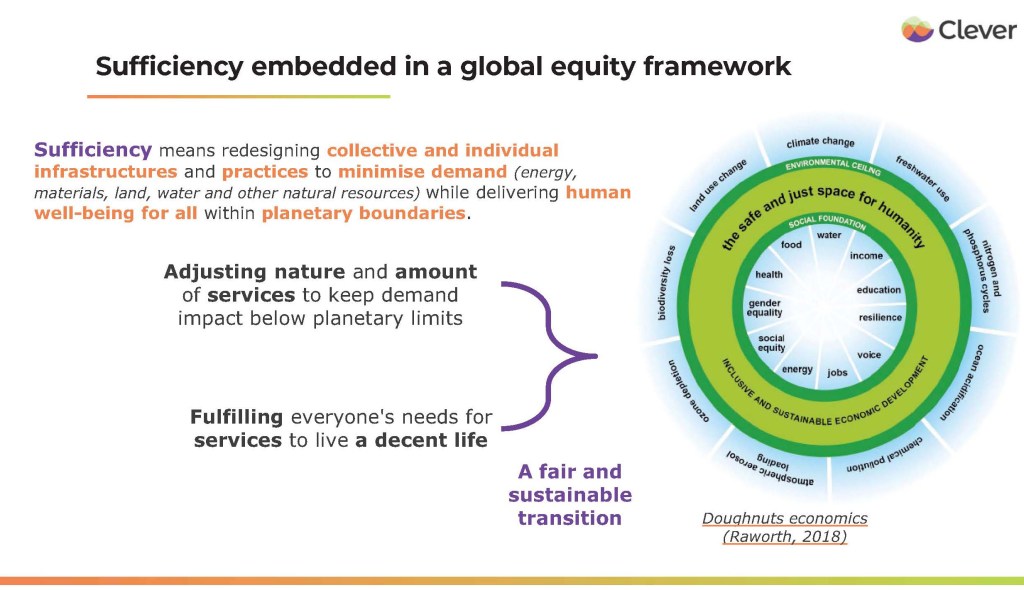

There are alternatives that shrink our overall energy and resource demand while fostering a more circular, sharing and equitable economy.

CLEVER –a Collaborative Low Energy Vision for the European Region projects that Europe can halve its energy consumption from 2019 and be carbon neutral by 2050, by focussing on sufficiency, efficiency and renewables (CLEVER, accessed 29/10/2024).

Closer to home and at much smaller scale, the Bega Valley is attempting to become Australia’s most circular economy (ABC, July 2024). So why not Aotearoa NZ?